Har Ki Dun trek diary part 2 of 3

“ You guys going up? Yes, yes, we go up. You may be going a lot higher than you think! ” — Don Whillans, to a Japanese party, while retreating off the north face of Eiger in a storm

Continued from Part 1 – Nainbagh to Taluka

There are days when my body sings and walking distances and inclines just fade away. Today was one of these days. I am carrying a full backpack complete with tent, sleeping bag and food for three days.

The menu? Paranthas, bread and peanut butter. If you don’t like peanut butter, too bad for you! Yet the thirteen kilos sit lightly on my back as I follow Dinesh’s footsteps.

I think part of this happy heart has to do with a clean trail (trekking groups and operators have not started moving on this trail yet) and the effervescent Supin River gurgling alongside our trail. As a trekker, I have a love-hate relationship with water. I love listening to the sound of water when I’m walking but I dread water crossings. As an element I find water to be the most unpredictable and uncontrollable of them all. Most of my trekking horror stories begin with “and there was this mountain stream”. Needless to say, this trekker is not a water nymph.

A couple of kilometres into the trek, we meet the first people on the trail. It is a group of villagers from Gangaad, the first village along the Har Ki Dun Trail. We stop for a chat and when the villagers see a couple of cameras dangling from my backpack, they assume that I am a reporter. Dinesh doesn’t help the cause by telling everyone who would listen – He writes about treks!

The villagers tell me that they plan to visit Mori for supplies. Since these villages lie deep inside the Govind Pashu Sanctuary, they have to get the road project sanctioned by the forest authorities. As we sit and discuss the politics of roads, it occurs to me that this is a tough nut to crack.

“Do we ruin a pristine stretch of nature so that people can get access to basics that we take for granted? Or do we protect nature and deny my own brethren. There is no easy answer to this dilemma.”

Villagers from Taluka do not want the road to go any further than their village, because if it does they lose their exalted status as the road head and it affects their livelihood. The villages not connected by road (Gangaad being one of them) are agitating for a road connection to ease their daily hardship.

“We live like cavemen here,” says Ravi, an aspiring politician and a member of the Youth Congress. “I approached Rahul Gandhi when he was here a few years ago and he promised to do something about it, but so far there has been no action.”

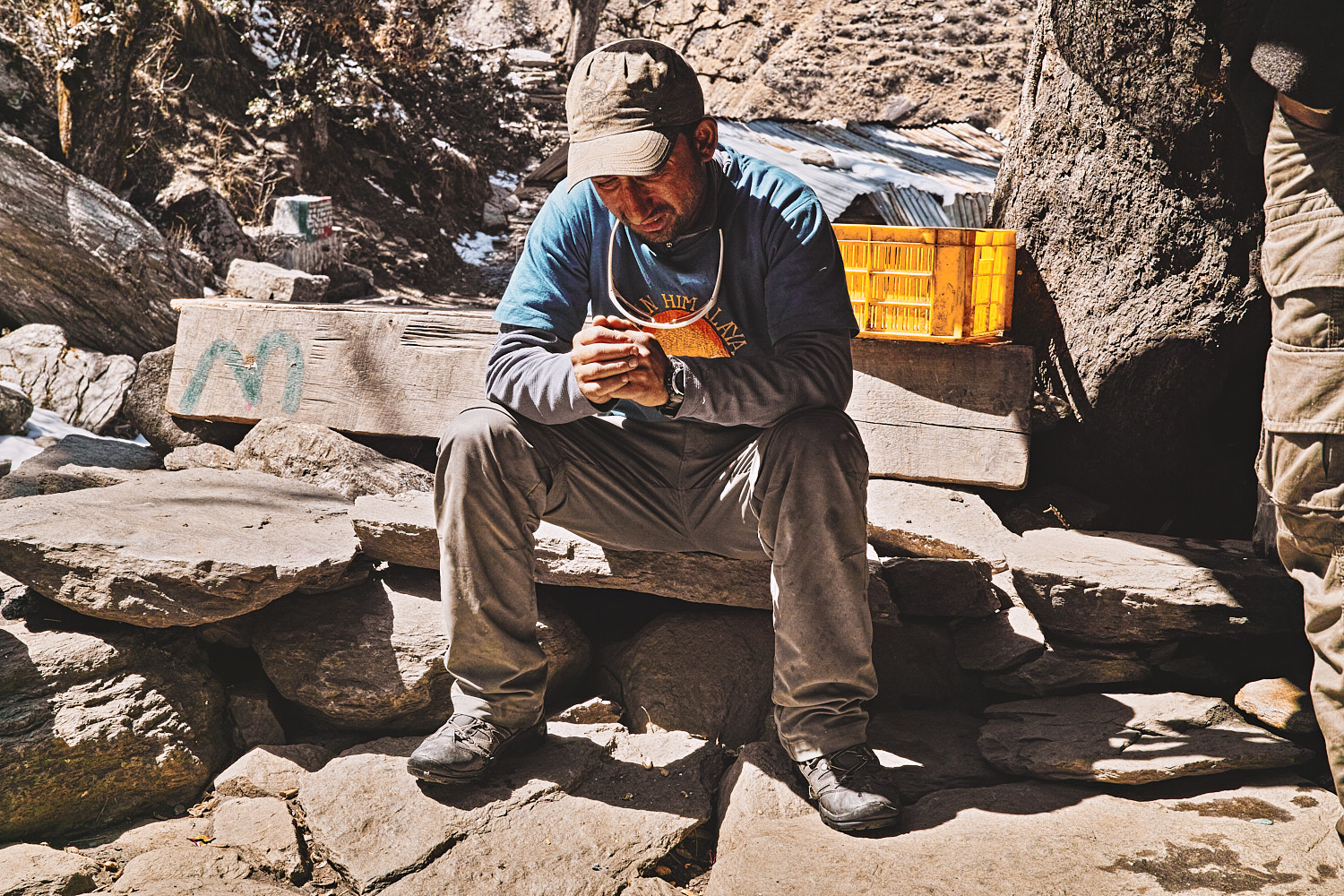

Gangaad is the first village on the Har Ki Dun trail, provided you haven’t taken a wrong turn and landed at Datmir. Something which Dinesh tells me a lot of trekkers do. Even I had accidentally stepped on the trail to Datmir before Dinesh corrected me. There is a tea shop along the trail just before Gangaad village. We stop for tea and some biscuits for Dinesh, who despite his lean frame could pack quite a bit of food as I was discovering. Ramesh was already drinking tea at the shop and headed back to Taluka. During the trekking season, he works as a trek guide for various large trekking operators. He had been sent by one of these operators to check the status of the trail and whether it was feasible for trekking groups to make it to Har Ki Dun. Yet the extraordinary snowfall this winter meant he had to turn back from just after Osla village. He sounded extremely dejected and demoralised. Wringing his hands, Ramesh says, “I am a local, if I can’t make it to Har Ki Dun, I don’t think any trekking group can. I’m not risking my life for these trekking companies that pay me peanuts.” Dinesh and I look at each other and the enormity of our endeavour starts to sink in now.

The snow gets heavier on the trail now as we approach the ugly concrete shed at “purani karat” or the old water mill. From this tri-junction, we have a choice of routes via Seema or Osla village. Dinesh suggests we go via Osla as his sister is married to a family in Osla and more importantly it means a free lunch. I wonder if this boy has something other than food on his mind all the time.

The final climb from purani karat to Osla after a rickety wooden bridge is the one that gets me. I am out of breath on the first zig zag and I am definitely huffing and puffing when I enter Osla. As I lean across my trekking pole, catching my breath, I am greeted by the sight of a weaver working on a hand loom. Osla is a sleepy Himalayan village which is more than 300 years old. A lot of trades and activity that we think are extinct can be found here. Handloom, two men saw, blacksmith, working with leather bellows…you name it.

The village bylines are mud swamps in places where the snow is melting and extremely slippery where it’s turned into ice. We gingerly walk through the village, subject to curious stares and kids who want to touch everything tied to my backpack. Since it is early March and the route to Har Ki Dun is “officially” closed, all the men sit around the village temple and play cards.

This temple once dedicated to Duryodhana, has now been rededicated to Someshwar Devta (an avatar of Lord Shiva). Why is a man so reviled through history worshipped in this beautiful land? Most of the villages in the Jaunsar-Bawar region look towards Duryodhana Maharaja as their benefactor deity, who is still approached with problems and pleas for justice. Legend has it that the mesmerised Kaurava prince appealed to Lord Mahasu, the reigning local deity, for this land. He loved this magnificent land & his people loved him back. It is said that when he was slain in the Battle of Kurukshetra, the villagers wept profusely, their tears creating the Tamas River-the river of Sorrow. Today, the river is called the Tons, but the villagers still don’t use the water for drinking. History is what is written by the victor. And it’s difficult to adjust our years of conditional learning. But when I asked why the Kaurav prince was worshipped, I was told that it is because he didn’t believe in or follow the deep-rooted caste system. How liberating it is to hear this! When we’ve walked past centuries & tomes of history, but not past our own casteist noses. The temple is a wooden three-chambered structure and even today the 5000-year-old ritual of Naubati, the traditional playing of the drums is conducted thrice a day in honour of the prince.

Dinesh’s sister (didi) welcomes us into her house and kitchen. Before we even get talking, a thali is plonked in front of us and rotis (unleavened bread) fresh from the “chulha” (earthen stove) are placed before us. Only once we’ve had our fill of the food are we allowed to talk. Didi is agitated when she hears that we are on our way to Har Ki Dun. She is suspicious of me and probably deems me to be the bad influence in this partnership. Dinesh takes the initiative and lays out the trekking gear that he’s been lent. It’s only after Didi sees the trekking boots and compares them to the tattered shoes Dinesh is wearing that she thaws out towards me. She piles us with extra rotis, pickle and even a couple of boiled eggs each for the trail. As we thank her and shoulder our backpacks to leave, she takes me aside and tells me to take good care of Dinesh.

The weather that had been sunny when we started from Taluka is now starting to get fickle. The snow on the ground is shin-deep just outside Osla and the wind is getting stronger. Our happy banter stops and we get in “plod ahead mode”. Heads down, caps, sunglasses and gloves on, one foot in front of the other. I take point after Osla because Dinesh doesn’t seem very comfortable walking in the snow despite his better boots. The second bridge after Osla has caved in due to the heavy snow. This means we have to leave the trail, descend to the stream and climb back up again. While on the trail, the depth of snow remains consistent, here off-trail it changes with every step. Sometimes I am stepping on a boulder underneath the snow and sometimes I sink waist deep. We manage to bodge through, but it takes us around an hour to get back up on the trail. With his energy reserves running on low, Dinesh starts staring wistfully back at Osla. I’m not doing too good either, the snow has got into my shoes despite the gaiters and even inside my pants. We dig out a couple of paranthas as we kick the snow out of our clothes. I give Dinesh the option to head back with no hard feelings, but he is resolute.

“We must head on! He says taking another bite from the now cold parantha.”

We don’t get very far though. The wind has turned into a gale now and while we’d planned to camp outside I decide it’s much safer to camp at the last lone house along the trail some fifteen minutes back. We retrace our steps and set up camp at the verandah of this locked out wooden house. Once our tent is up is a relatively sheltered nook, I step out to watch the sunset over Kedarkanta peak. There’s nothing to do post sunset, and we have a quick dinner (bread liberally piled with peanut butter) and get into our sleeping bags. I hope the wind blows away the clouds… is the last thought in my head as my eyes close.

Does the weather clear out tomorrow? Do we get a chance to be the first team to make it to Har Ki Dun? Find out in Part 3 tomorrow.